February 24, 2022 | Category: Values Orientation

The NSN acknowledges that human trafficking is horrific, and is an extension of rather than an exception to the range of exploitation inherent in capitalist systems of labor. What we mean by this can be illustrated by comparing these two helpful graphics by Joel Quirk.

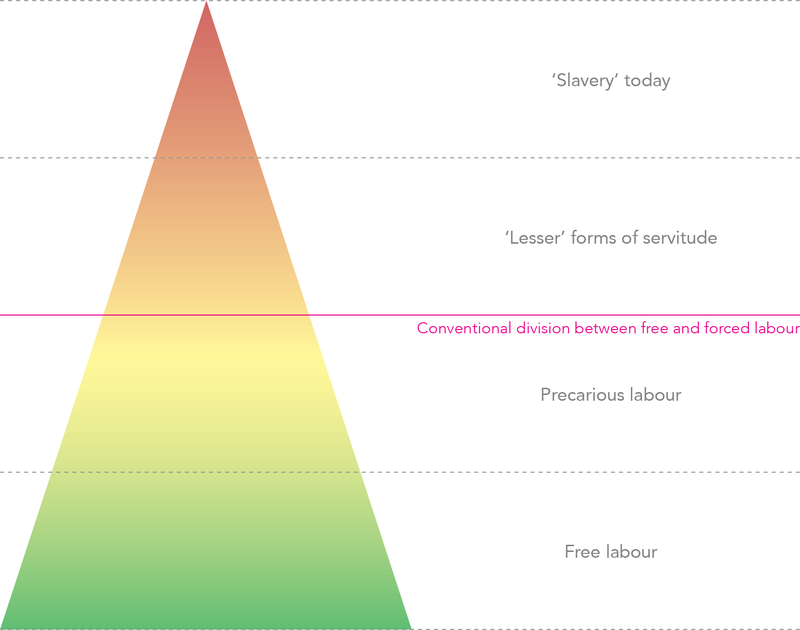

This first graphic shows the way many people in the United States (and elsewhere) think of the distinction between free and forced labor.

In this model, we assume that most people’s labor is free and that significantly fewer people are engaging in precarious labor than in free labor. The smallest amount of people in this model are engaging in what we would consider “forced labor,” with a small number engaging in a “lesser” form of servitude and an even smaller number experiencing trafficking or slavery. In this model, entirely free labor – chosen by people who have options and still freely choose the work that they do – is assumed to be the norm for most people in our culture.

When we assume this model, we fail to acknowledge the ways in which most people don’t have a lot of options about the work they do. A significant majority of Americans earn just enough to pay their bills each month and that 3 in 10 have no emergency savings. (Link) Additionally, 17% of Americans aren’t able to pay all their bills each month, and 12% would have no way to cover an emergency $400 expense (not even using a predatory payday loan). (Link) On top of this, intersecting oppressions such as racism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny mean that the impacts of poverty are felt more strongly by people with marginalized identities, who are more likely to live in areas with concentrated poverty and have fewer options for work.

Under these circumstances and with so few options, people working in a variety of economies and forms of labor might not be able to choose from a wide variety of appealing work options, and many are forced (by economic circumstances) to do work that might harm them, or in which they experience coercive or exploitative power dynamics from their employer.

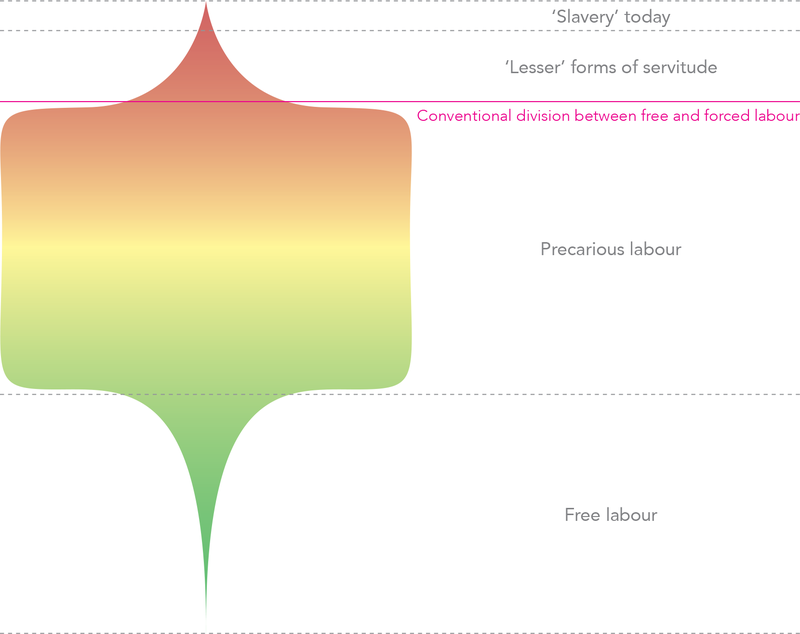

In reality, all kinds of labor exist along a range, with forced/trafficked/enslaved labor and freely chosen labor being in the minority, and the vast majority of people engaged in precarious labor. This includes any positions where workers do not have secure, stable employee status that does not put their wellbeing at odds with their economic survival. This includes contract and temporary work, work as an “independent contractor,” and work in informal or street economies. It also includes work in which employees cannot leave without repercussions, cannot take a sick or family day without risking unpaid bills, or are pressured due to economic necessity to do work or tolerate employment practices that cause them harm.

Below is a more realistic model of the relationship between free and forced labor, in which we acknowledge that a significant number of people are working under conditions that contain a legal amount of exploitative practices and economic coercion.

A certain amount of exploitation is not only legal but normalized in the United States, and normalization of exploitative labor practices increases vulnerability to trafficking. This is why the labor movement is so essential for workers, and also why its efforts have often been resisted by employers. Economic necessity breeds desperation which leads to compliant workers, and compliant workers are less likely to be able to push back against unfair labor practices.

We recognize that immigrants and non-citizens are especially vulnerable to exploitation under these systems. Additionally, current immigration policy creates vulnerability: Tying visa protections to a specific employer limits worker rights and opens the door to further exploitation for both labor and sex trafficking.

We work to transform these systems of exploitation while simultaneously engaging in harm reduction to mitigate their impacts. In the US, many people who do not have generational wealth, access to a path to immigration status, privileged identities, access to education or professional networks, or social supports have limited options for the labor they do. As a result, the must engage in work that may negatively impact them in a variety of ways in order to feed their families and stay housed, which can include physical, psychological, and/or spiritual harm.

The remedy to this is transformation of our inherently oppressive economic, humanitarian, immigration, and social systems. We deplore the economic and social circumstances that leave people to choose precarious work out of economic necessity and acknowledge that this form of limited choice is not unique to criminalized economies.

Check back soon to see the sixth in our values orientation series, “Criminalization,” or view our full values statement here.